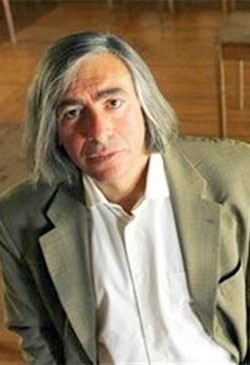

Manuel da Silva Ramos was born in 1947 in Covilhã (Refúgio), the town where he concluded his lyceum studies. He studied Law at the University of Lisbon for four years before his exile in France. He lived in Toulouse between 1970 and 1997. Upon his return to Portugal in 1997, he began a decade of intense literary activity, publishing several novels dealing with certain aspects of the exile narrative, emigration, colonization and the Portuguese diaspora. In some recent works, displacement is also seen as the journey of literary creation, designed to incorporate the geographic and cultural spaces into the literary space. In his debut book, Os Três Seios de Nouvélia (1969, Almeida Garret Novelistic Award), wandering around Lisbon is a starting point to the extensive set of travels in the spaces of the world and writing which his work would come to materialize.

The theme of ‘Portugality’ dominates the narrative and typographic experimentation of his initial works. Co-written with Alface, the Tuga trilogy includes the novels Os Lusíadas (1977), As Noites Brancas do Papa Negro (1982) and Beijinhos (1996). Departing, living in another place and returning define the trilogy’s cycle. In the three novels, the physical journey is absorbed into the journey within the mechanisms of paronomasia of language and speech. The text presents itself to the reader as a journey of decoding its associative verbivocovisuality, overloaded with anal and genital images. The parodic procedures, both stylistically and narratively, are particularly evident in Os Lusíadas. The trilogy’s Joycean heritage is visible in its verbal inventiveness, in the sexual and scatological comicality, in the parodic and meta-referential irony, and in a Rabelaisian maximalism. The journey and the wandering reappear in other works like Viagem com Branco no Bolso (2000) or Jesus – The Last Adventure of Franz Kafka (2002). His writing can be said to be itinerant, with an attending double meaning: that of the constant travelling through identity creating spaces, and that of the journey through mental and verbal spaces which reproduce ways of thinking, speaking and creating the experience of the world.

Sarcastic irony and literary parody are, sometimes hilariously, part of his solo works. His savagely metaphorical creative skill alternates between the lyrical and the narrative, in long or short forms — an instability of style and genre already detected by Óscar Lopes in 1969. The omnivorous torrent of his inner monologues shapes the sexist and racist structures of the Lusitanian macho ideology, as well as a certain mental atavism in the Fátima-Fado–Football trinity. The portrayal of the erotic body is associated with forms of figuration which work almost always as objectifiers or subordinators of women. Similarly, the character of the black man emerges frequently in the various verbal manifestations produced by the visceral fear of the other in the colonial unconscious. These and other archetypes, such as the tavern and the brothel, materialize certain ghosts of power in the Lusitanian ideology, proving its virulent and persistent nature even in a Europeanised and globalized society.

The option for the principle of surrealization and verbal deformation of the real is visible in the almost arbitrary relation that his novels establish between facts and fiction. In works like Viagem com Branco no Bolso (2000), Café Montalto (2003) and A Ponte Submersa (2007), for instance, Manuel da Silva Ramos bases himself on a historic or journalistic investigation of individuals and events, but is unconcerned with reconstitution or verisimilitude. In Viagem com Branco no Bolso (2000), the characters of the Dwarf of Arcozelo (António Lopes Ferreira, 1943-1989, 75 cm) and the Giant of Manjacaze (Gabriel Estêvão Mondlane, 1945-1990, 2.45 m), which connect the North of Portugal with Mozambique, work as caricatures of cultural and social practices of the fascist and colonialist Portugality. In Café Montalto (2003), several photographs are used as traces of the wool industry and the social and economic life in Covilhã between 1963 and 1986. In A Ponte Submersa (2007), the starting point is a set of murders that took place in Santa Comba Dão. However, documents and testimonies were appropriated and redefined by the discursive order of representation and by the obsessive figures of that discourse, among which are notable the figures of wandering, the whore, the macho, the labourer, the boss, the dwarf, the black man, the foreigner or the portuga.

Through the torrent of words one can understand the ideological dimension of fiction as a specific technique for deforming the world. The ghosts of fascism, racism, sexism or liberalism are embodied in their own linguistic structures, and not merely in described or recalled characters, spaces and environments. Language emerges as speech act of the phallus, an implement of power and of the violence that individuals exert and suffer. Occasionally, the invasive voice of the writer himself, or of one of his figures, interacts with the internal plane of the narrative, undoing the realist transparency or the caricature-like logic of the framing. The presence of rain as a narrator in A Ponte Submersa is another example of the coming together of the narrative and the discursive. Therefore, readers can only believe in the ‘verbifying’ mechanism of language and writing, in its ability to make fiction factual and present the real as a comic parody and alienated speech. Prisoners to the ideology of form and language that they are, the texts combine the implausibility of narrative self-reflexivity with the self-surprised laugher of the word with itself and the affective pathos of the inner monologue.

source: https://ulysseias.ilcml.com/